FilmmakerLife Magazine Presents

In the world of filmmaking, where stories have the power to transcend borders and cultures, there are certain tales that possess a remarkable ability to resonate with audiences from every corner of the globe. Such is the case with “RED FAUST,” a cinematic journey that not only encapsulates the rich history of Hungarian martyrs but also delves into the intricate interplay between the roles we inhabit within ourselves. We had the privilege to interview the acclaimed filmmaker Zsolt Pozsgai to delve into the transformative process of bringing this unique story to life on the silver screen.

- Can you share the journey of adapting the play “RED FAUST” into a film, and what inspired you to undertake this project?

In my country, Hungary, it’s not a rare evening when a successful theatre production is turned into a TV play or a TV movie, or even a feature film. The title of my original drama is “I Love You, Faust,” and it is about one of the most important figures in 20th-century Hungarian history. A bishop who consistently spoke out against hatred, violence, and terror during the wars and the communist dictatorship. For this reason, he became a nuisance to all the new political regimes and was frequently imprisoned. However, the people released him several times, and he resumed his work each time. Towards the end of his life, even the Roman Pontiff was uncomfortable with the bishop’s continued existence and work, attempting to silence him. The Hungarian people hold this martyred bishop in great esteem. The drama about him has been continuously staged in Budapest for twenty years with the same cast. I was approached by Hungarian television to create the film version, but they also wanted to dictate how I should write the script – which characters to omit, especially those who were disliked by politicians, and whose roles I should reassign. I was not prepared to comply with those demands, nor was I willing to create a biopic that would span his entire life from childhood to death. I don’t believe in that approach. I believe that in the life of every historical figure, there are one or more events or periods that can be portrayed in a way that encapsulates the essence of the protagonist’s life without changing actors or ageing them as the story progresses. Of course, there have been successful films made with this concept, but this is not one of them. In both the drama and the film, the bishop is placed in a prison cell in 1944 alongside the most famous male actor of the era, Jávor Pal. This is a historical fact. By depicting their encounter, I was able to portray the bishop’s activities, sufferings, and joys. The actor, like a Mephisto, reveals to the bishop what his future will hold once released from prison, the tragedies he will have to endure, and then he must make a choice: to continue and face them or to commit suicide. Subsequently, the actor takes on several roles, as do other actors in the film. Five actors portray approximately twenty roles. I have maintained this dramaturgy in the film. When I expressed my desire to make the film according to my vision, my friends supported me. These included professional artists, cinematographers, visual designers, and other artists, as well as world-class film technology companies that provided me with the best camera and lighting technology free of charge. So, we had access to the best technology for our work. With only a total of $15,000 in cash available, I had to consider where we could shoot the footage. That’s when the House of Terror Museum in Budapest was completed – a modern, state-of-the-art museum unparalleled in Europe. Given its six-story structure portraying the fascist and communist dictatorships, the interior spaces were well-suited for depicting a man’s life without having to leave the museum premises. The prisons, video installations, the military tank inside the building, and even the glass lift were all suitable. So, I set the script within these spaces, and that’s how we filmed the project, which, at the time, was still a TV drama. In total, we were able to work for four nights, from the museum’s closing time until its morning opening. This required significant organisation and precision from everyone involved. Alongside the cameraman, Mark Győri, and the chief lighting technician, we carefully planned and set up scenes in every room of the museum, from the attic to the cellar. These spaces became the backdrop for the main character’s life.

- As a filmmaker, could you delve into how the transition from a stage production to a film impacted the storytelling of “RED FAUST”?

What we say on stage in the theatre must be seen in the film. The acting is magnified in the film, and certain dialogues become redundant. At that time, I had already written nearly two hundred scripts for television or film, which I had realized, and it was more of a pleasure, a challenge than a difficulty. Nearly half of the drama had to be discarded, as the laws of film are quite different. The dialogue remains the primary element, but you can perceive a whole other world in the background. This duality imparts the film’s style. At the time, we didn’t anticipate it being a feature film; we were thinking in terms of a TV drama. It’s very interesting how an actor needs to be taught to portray a stage role that has been performed for a very long time in a completely distinct manner in a film. The gestures, accents, and even the volume differ. We rely much more on movements, eye contact, and playing with the body instead of words. However, by collaborating with exceptionally talented actors, we managed to make this transition swiftly. Additionally, there were scenes in the play that would have been unnecessary for the film, so we omitted those.

- Photography often plays a pivotal role in the filmmaking process. How did Zsolt Eöri Szabó’s involvement as a photographer impact the film’s overall visual storytelling, particularly in capturing the essence of the House of Terror Museum?

Márk Győri and I have collaborated on several occasions; we are familiar with each other’s thoughts. He also enjoys working in abstract spaces, transitioning from the real to the unreal world. He was genuinely enthusiastic about the task. Each room and space presented a significant challenge for him—how to manage the lighting and which aspects to emphasize. For instance, if I mentioned that we were filming a clandestine meeting, my intention was for the audience to feel like they were observing the scene through a keyhole, and Márk Győri executed this brilliantly. When we needed a location in the museum to represent the Roman papal suite, we found one. Similarly, when we had to portray a surreal journey and had the two main characters frequently ride the glass elevator, we later edited it to appear as one continuous journey.

- “RED FAUST” was shot in just four nights due to the museum’s daytime visitors. Could you discuss the challenges and benefits of such a condensed shooting schedule for a project of this nature?

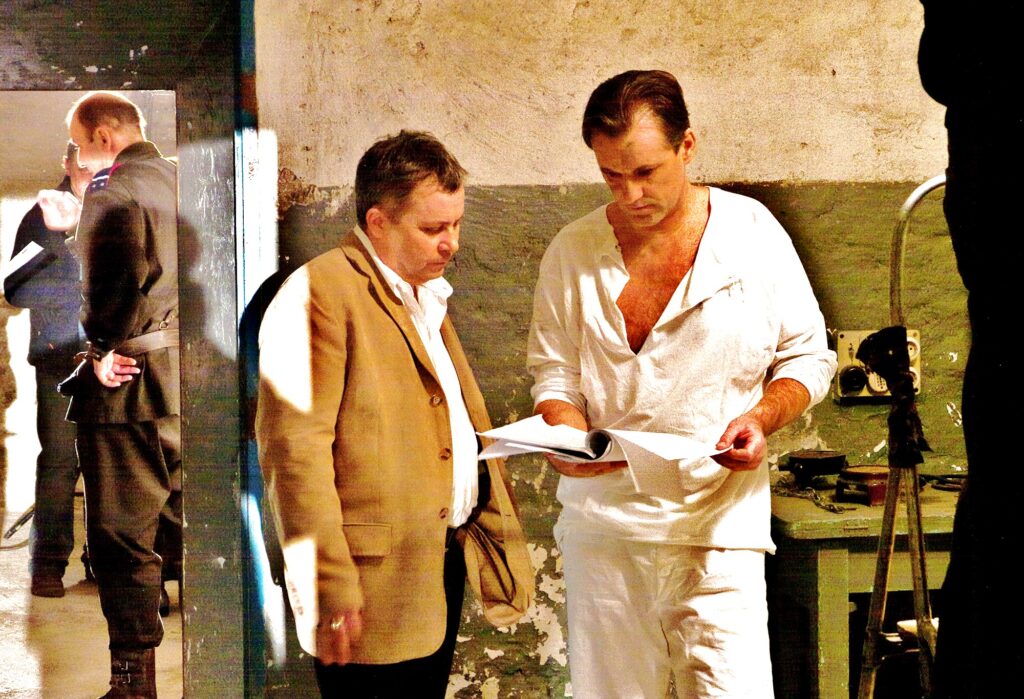

Many times I had to work quickly, often with only a few days. But never so few. As a director, I had to be prepared for every situation. With the technical crew, we had to determine precisely what would happen at each location, the type of camera movements we were planning, and the lighting effects we intended to use. We also had to consider how to capture professional-quality sound recordings. The actors were well-prepared; we rarely had to halt shooting due to forgotten lines. I worried about whether the artists and the crew could physically endure from eight in the evening until eight in the morning, especially the two main actors who appeared in the film almost continuously without rest. It wasn’t easy. One morning, around three o’clock, my friend Adam Lux, who portrayed the main character, collapsed, trembling and struggling to breathe. We were deeply concerned and immediately called for an ambulance and a doctor. However, the actor insisted on continuing. He requested injections, and after a brief rest, he resumed working. I’ve shared a photo of him lying on the floor, wrapped in a warmer garment, with his concerned partner kneeling beside him. Everyone waited for the doctor, and he continued working until morning. I had the opportunity to collaborate with exceptional artists with high energy levels. We knew we had a limited time to make the film, and that brought our team together. Everyone was passionate about and believed in what we were doing, and that’s a tremendous source of strength.

- The relationship between the Priest and the Actor seems to be a central theme in the film. Can you explain how this dynamic is explored, and why it resonates universally across different cultures?

Obviously, the main character and his story are known to Hungarian audiences, but I enjoy creating films that can be appreciated worldwide. Not just in film but also in theater. Ten of my plays are currently being performed somewhere around the world, in theatres from London to India. In this film, it’s the historical reality, the actual encounter, that intrigued me. It’s a dialogue between a Priest and an Actor about a period, about life, about one’s own life. And I believe we all possess this duality: within us, there’s a priest representing faith, conviction, someone who prefers solitude, solitary prayer, and living in that faith. Simultaneously, there’s an actor, for whom success and applause are paramount. To be present everywhere. These are two opposing desires. The choice of whether to behave as a priest or an actor in various life situations falls upon us. It’s often not an easy decision to make. To me, this film revolves around that theme. However, of course, viewers can also learn about a very intriguing historical situation in Hungary during the era of wars and dictatorships, which might pique their interest beyond the film’s philosophy. And the list goes on. I’ve had the opportunity to attend numerous festivals, and I’ve found that even in a Buddhist country, people comprehend the film, a film about a Catholic bishop. But why wouldn’t they? We are all human beings on this planet.

6. Your decision to reject political demands during the film’s creation seems to have been pivotal. How did this decision influence the film’s overall message and impact?

I believe that politics have no place in art because politics are subject to change, while a film you’ve created remains unchanged. In Hungary, politics attempt to influence the art of filmmaking, often entrusting big-budget films to individuals with no prior experience, thereby causing significant harm to Hungarian cinema. I am an independent film director, and I hold a deep appreciation for the world of independent films, where producers refrain from dictating the actions of the cast and refrain from interfering in the creative process. Furthermore, in these productions, money’s role is typically a primary concern, focusing on how much profit a producer and their associates can extract from a film. I’ve independently produced my own films on several occasions, so I am acutely aware of the costs involved. The funds we receive or generate have been allocated towards compensating the crew and the artists. Consequently, I receive an increasing number of projects from organizations or private individuals who genuinely support the art of filmmaking rather than being solely driven by profit motives.

7. The film’s journey from a TV project to a feature film is intriguing. Could you discuss the process of reworking and polishing “RED FAUST” to transform it into a full-fledged feature with international appeal?

Originally, I wasn’t the producer of the film but rather an individual with no interest in the film’s fate or its future. For twelve years, we requested multilingual subtitles to transform a TV drama into a feature film, but he consistently refused. When our contract expired last year, I assumed ownership of the film, and I immediately started working on it. We conducted additional editing on the film, added subtitles, revamped the lighting, and improved the sound quality. All of these efforts were necessary because my previous two films, “THE DEVOTED” and “DARKING WAY,” had received numerous festival awards, and festivals were increasingly requesting new films from me. Furthermore, this film, “RED FAUST,” has gained popularity not only among festivals but also among distributors. For instance, in our most recent success in Zimbabwe, the film was broadcast on television there. For me, there’s no greater pleasure than that.

8. Building upon the success of “RED FAUST,” How do you envision your future projects aligning with your artistic vision and the impactful storytelling that defines your filmmaking?

After the success of these three films, I have received several requests. I’m currently working on a documentary, and it’s in progress. I also have a historical film in development, set in the 14th century, as well as another project focused on a contemporary event related to the subject of migrants. Additionally, I have a strong desire to create a genuine ballet film that incorporates a compelling narrative. There are plenty of themes and ideas to explore, and I am actively seeking partners from around the world who share a passion for producing truly independent films to collaborate with me. They say that you don’t age when you have a multitude of plans waiting to be brought to life. If that’s the case, I anticipate a long and fulfilling life ahead.

Connect with Zsolt Pozsgai