From the intimate lights of the theater to the expansive canvas of cinema, Don Thompson has spent decades crafting stories that challenge, inspire, and endure. As a playwright, filmmaker, producer, and educator, his work seamlessly weaves together spirituality, political consciousness, and cultural preservation. With projects showcased at prestigious festivals like Sundance, Cannes, and Berlin, and a career that bridges art and activism, Thompson continues to push the boundaries of independent cinema. In this conversation, he reflects on the milestones, challenges, and driving passions that shape his creative journey.

You began your journey as a playwright in the 1980s before transitioning to cinema. What lessons from theater still influence your filmmaking today?

What I love about theater is its intimacy and directness—or at least its potential to have those qualities. My plays have typically been staged in smaller, more intimate settings, although at times they have also been staged in more proscenium style theaters as well. The point is that when a theater piece is intimate, the acting can approach what you can find in film. Film, regardless of the fact that it is often hijacked by action and quick editing in our modern era, can and should be a highly intimate art form. The closeup is the quintessential form of acting intimacy. The greatest film actors achieve this intimacy, almost imperceptibly. They have a naturalness and an openness about them. So it is the potential for intimacy in both theater and film acting that has a pervasive influence on me. To create a connection with the audience that is unique and opens up the door for empathy, awareness, and human connection.

Was there a specific moment or project that made you say, “It’s time to tell stories through film”?

My desire to tell stories through film actually, believe it or not, predates my playwriting. In high school and in my early college days, I worked on a couple of short film projects with my brother. I moved into theater as a request from my brother to adapt Frank Herbert’s Dune Messiah into a play. Almost by a fluke, my brother (who was quite young at the time), received permission from Frank Herbert to adapt the author’s Dune Messiah into a play for his college theater in the 1980s. That story went on, eventually, to be developed (not by us) into a big budget film that is apparently slated for release in 2026. So, we were a little ahead of the curve.

My other big break in theater was also for a friend, who was looking for a writer to help her out with some scene work at the Ensemble Studio Theater, Los Angeles. We began developing scenes around a common theme of nuclear war. The artistic director of the theater, John Randolph (as well as his wife, Sarah Cunningham, now both long gone), loved the material and wanted to stage it. The result was my first staged play, L.A. Book of the Dead, which received positive press attention from Dan Sullivan of the Los Angeles Times, who wrote a very generous review about the piece. So the evolution of my involvement in theater was almost tangential, with friends or relatives asking me to get involved. Later, with Tibet Does Not Exist, it was more of a deliberate effort on the part of my wife and myself to produce a play.

Many of your works blend spirituality, political awareness, and cultural preservation. How do you balance these elements while keeping the audience deeply engaged?

I appreciate that question. It is a balancing act. I typically write what I want to write, without much consideration for who might like or dislike the material. I don’t intentionally write to have people dislike a story, but sometimes doing what I want does run counter to what might be considered popular or ‘correct’. What has been fascinating to me is that, for the most part, my instincts have been good in that other people have also been concerned about the topics that I have delved into, and the result is that often I found myself with a group of others that is ‘launching’ the issue into the public sphere. This was the case with L.A. Book of the Dead (nuclear war) and Tibet Does Not Exist (the China-Tibet issue). So at times there seems to be part of me that taps into the cultural zeitgeist in an attempt to express what is happening in the moment.

I also will use those topics to delve into what you might call the folly of being human. What I mean by that is that there is a certain absurdity to the human condition, although that ‘condition’ is very important to all of us experiencing our lives. I do believe the reality of love and compassion, for me at least, points the way out of absurdity and toward moral clarity. At any rate, when you are confronted with absurd human behavior, such as war, torture, out-of-control nuclear arms, and other abuses that make no sense, my natural reaction is to say ‘hey, there might be a different way to do things ’. So I bring whatever tools of perception I have to bear into the effort, including, as you allude to, spirituality, political awareness, and the sense that we should preserve what is valuable rather than destroying pretty much everything that stands in the way of supposed human progress, a progress that at times is dubious. But, I must say that I believe in progress and human evolution. But I do often feel humanity has gone down the wrong path in terms of defining what that progress is. Our current path, it seems, leads us to the robotic human. This may not be the best path for humanity.

Works like Tibet Does Not Exist and Tibet in Song reveal your commitment to cultural and human rights issues. What personal impact did working on such sensitive and powerful topics have on you?

I’ve always had an affinity for Buddhism. I remember my cinematographer on Clouds, Gary Lindsay, at one point early in our friendship, mentioned to me he had become a Buddhist. I had read spiritual works, such as Autobiography of a Yogi, and been deeply impressed. I felt like I wanted to be involved with the general mission of investigating what ancient Buddhist (and Eastern) traditions could say to our modern (often cynical) views. The impact of working on these projects, particularly Tibet Does Not Exist, was profound primarily in the states of mind the process of writing them evoked. For example, with Tibet Does Not Exist, I would be riding on the train back and forth to New York, and literally go into states of reverie where I would almost ‘feel’ the play. I would then more or less transcribe the play from this felt sense of stillness and reverie. If this sounds counter to a more technical approach to writing, you’re right, it is! I used the same approach with The God of This World, particularly in the initial drafts. Later drafts were more ‘technical’ in that they came out of readings, working with actors and a director, and so on. So The God of This World was more collaborative in that way. Tibet Does Not Exist was performed almost exactly as I wrote it, without a lot of rewrites and changes. So, to answer your question, working on these kinds of projects, particularly Tibet Does Not Exist, evoked a sense of reverie in me that was itself a spiritual experience in a very real way.

Your films have reached platforms like Sundance, Cannes, and Berlin. In your view, what is the greatest challenge independent cinema faces today in gaining such recognition?

Getting back to the question regarding the socially-relevant plays, the greatest challenge I believe for any artist is to actually figure out what is important. Not necessarily what is popular. That is fairly easy. Not necessarily what is commercial, or potentially commercial. Rather, what is important should be the primary question in all one’s work, I believe.

What is important is not necessarily what you may want to do personally. For example, part of me would love to write and direct a very popular Hollywood style movie that was highly entertaining and made a ton of money and then allowed me to retire to a multi-million dollar home in Hawaii. That has not happened, probably, because it is not as important to me as other things, such as, for example, climate change. Speaking of the importance of that issue, I have recently stopped focusing so much on my film and theater career and went back to get a PhD so I can write a research study about climate change because that again, to me, is important. I truly believe that this inner sense of what is important has an impact on what I find is the reality of my life.

Now, as far as the films that have been selected for those top-tier festivals, they were all, to me, important films. Let’s take Yomeddine for example. I watched about two minutes of a teaser for that film very early on in its development and believed it was an imporatant film. Apparently, according to the producer, I was one of the first people (outside of the filmmaker) to feel this way. Yomeddine went on to win a prize at Cannes because it was apparent that the story was important and human. It was essentially about suffering and how suffering can be alleviated through compassion. I do believe this is an important topic.

If you could return to your very first film project, what advice would you give yourself with the knowledge you have now?

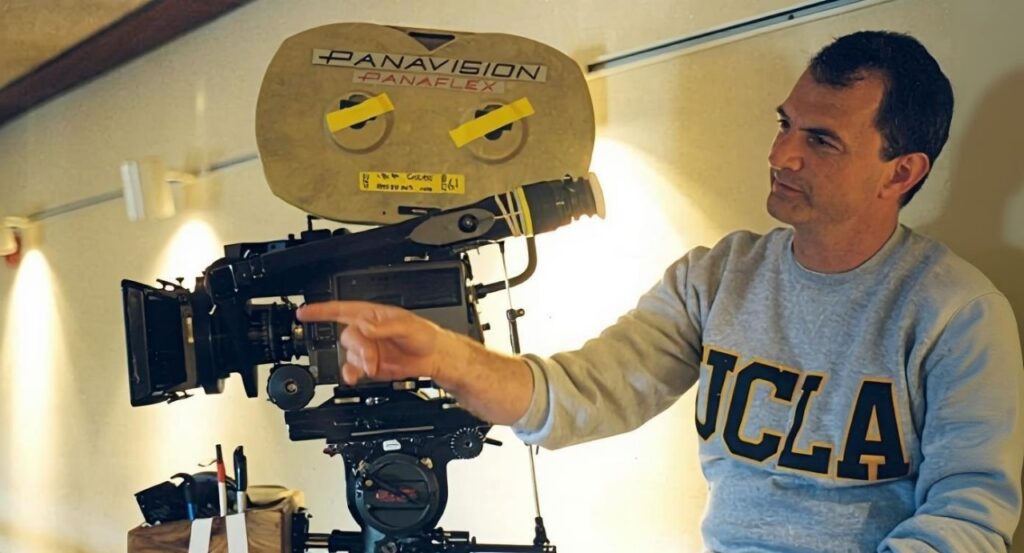

I believe that I was well intended with, for example, Clouds, an ambitious film in many ways, but one that fell short on the execution side of the equation. But much of it was executed quite well. One thing I learned is that you can get too close to the material and sometimes it’s good, perhaps essential, to have a more objective eye to critique the project at all phases, and to have the humility to listen to some of that criticism. That said, Clouds in many ways was a very pure film. The purity of the film may have been an issue with some people. What I mean by that is that it was an affront to their sensibilities. But then, I feel the film was meant to be as it is. So perhaps it was successful in that way. For example, people complained about some of the stilted dialogue. But the dialogue was intended to be ‘stilted’ in a way. To be clear, I felt it was important to make a film that was ‘anti-Hollywood’ in style and theme. As a result, one might not expect the film to receieve universal acclaim. My experience with Clouds reminded me of of Charles Laughton’s first and only film as a director, The Night of the Hunter. Initially dismissed, it is now considered a classic. Apparently, Laughton had some ideas about what film could be that ran counter to the overall view of the critics at the time of its release.

Some of your work, like Clouds, has been described as ahead of its time. How do you recognize a story worth telling even if audiences might not yet be ready for it?

Clouds was an interesting experiment. I recently started circulating the film around film festivals, after twenty-five years, to get some sense of how people might react to the film in our current time. I also did some re-edits on the film and selected different music. Although I loved the original music, it did not really match what I had originally envisioned. This recent re-launch to film festivals (mostly smaller festivals, to be clear) has seen the film garner new recognition for ‘best experimental film’. I do believe the film does deserve some recognition on this front, so I’m grateful that some of these festival directors agree. Also, another note about the re-launch. Like many other situations in my life, it was the result of a request. A festival in Sweden requested to view the film and I sent it along. I had been mulling around in my head about a ‘25th anniversary relaunch’ of some of the changes I did to the film, and the current (2025) festival situation more or less organically presented itself to me. It led to other things, such as this interview.

Beyond creating, you teach and mentor emerging talents. What is the most important lesson you aim to pass on about telling stories with purpose?

Again, as mentioned before, I do believe it is key to do what is important. Let’s dive into that a little deeper. I believe for the most commercial, successful filmmakers that are directing action movies and films that are popular, that is what is important to those people. They may not care about art per se. And that is OK. They might direct a horror film because that is important to them and they are passionate about that. And it may even be an artistic horror film. I applaud that. That said, most of the students I’ve worked with are interested in their own personal stories. This has mostly been through the UCLA Alumni Mentor program where I have mentored a few dozen people. As a whole, these people are not so commercially minded—those types of people don’t usually sign up to mentor with me. As you hint, some filmmakers believe there can and should be a purpose in their filmmaking. A purpose outside of popularity and commerciality. So once in a while these people come knocking on my door and want to learn something. That said, most of my recent teaching (for example, at Johns Hopkins) is of a more academic flavor, although I do also still teach screenwriting on occasion. I do love to teach. You can find truth in all of it. You can find the truth of a story, or an academic theory. Either way, finding the truth of something can be quite an astounding thing. The process continues to leave me spellbound. So, I try to convey that love of teaching to my students. But not by saying those words necessarily. Rather, by demonstrating those words. By living them.

Among all your works, is there one project that irreversibly changed the way you see the world?

Each project has changed me in profound ways. So it’s hard to say. Those films that have put me closer to my higher sense of purpose tend to change me. It is hard to explain. It is you might say a ‘flow’ state. There is actually such a thing in psychology, and even a communications theory. So whatever project puts me into this state of flow changes me as it allows me to be in the moment and tap into the creativity that is evident, I believe, everywhere. It is not really ‘yours’. You are a vehicle for the Flow. The world, in this way, is effulgent with the creative. I believe if more people sensed that and lived like that, we might have a different world. But people as a rule are afraid of those kinds of states of mind because they portend a kind a chaos and letting go that most people do not want to experience and are quite frankly afraid of. By the way, any talent I might have along these lines doesn’t make me any better than anyone else. If I felt that way I do believe I would shut off the flow. The flow is essentially humble.

With Where to Land on the horizon, what emotions and reflections do you hope audiences will carry with them after the credits roll?

Hal Hartley (director of Where to Land) is a very special human being. He is multi-talented, and, in many ways, overlooked. That said, he is an artist and manages to make his way as an artist by doing (it seems to me) what is important to him and what he loves. Ideally, that shines through the story and the film. I believe it does.

Don Thompson’s journey is one of courage, persistence, and vision—an artist who refuses to separate art from purpose. Whether on stage or on screen, his work invites audiences to question, to feel, and to see the world through a more compassionate lens. As he prepares for his next chapter, one thing remains certain: his stories will continue to resonate long after the lights go down.